Record of Learning Rust | Part 1 of 2

Common Programming Concepts

Variables and Mutability

Mutability

默认情况下,变量是不可变的(immutable)

声明一个可变变量:

1 | |

Constant

常量当然不能用mut修饰。

声明常量:

1 | |

常量在程序运行过程中都有效。建议将程序中用到的**硬编码(hardcode)**值设为常量

变量遮蔽(shadow)

重复使用let关键字来遮蔽变量

Data Types

Rust 是一个**静态类型(statically typed)**的语言,必须在编译器知道所有变量的类型。

两类数据类型:

- 标量类型 (scalar)

- 复合类型 (compound)

Scalar Types

- 整型

- 浮点型

- 布尔型

- 字符

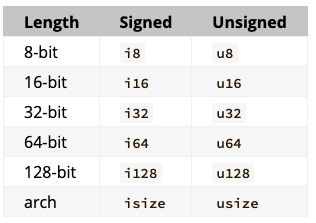

integer

isize 和 usize 主要应用场景是作为某些集合的索引

除了字节字面量之外的所有的数字字面量都允许都允许使用类型后缀。如114514u32

==Integer Literals==

| Number literals | Example |

|---|---|

| Decimal | 98_222 |

| Hex | 0xff |

| Octal | 0o77 |

| Binary | 0b1111_0000 |

Byte (u8 only) |

b'A' |

整型溢出(intefer overflow)在debug模式编译时,会出现compile time panic

在release模式构建时,不检测。但如果发生溢出,会进行

two's complement wrapping的操作。如在 u8 的情况下,256变成0,257变成1。显示地应对溢出的发生,使用标准库针对原始数字类型的方法:

wrapping_*checked_*overflowing_*saturating_*

Floating-Point Types

基本类型:

f32f64(default)

Numeric Operation

基本的数学运算:

- 加减乘除运算

- 取模

The Boolean Type

可使用字面量显式赋值:let t = true;

The Character Type

Example:

1 | |

是 unicode 值,但是Rust的字符概念和直观上的不一致。

Compound Types

tuplearray

tuple

fixed-length

declaration

1 | |

access element in an array

1 | |

array

Compared to tuple, every element in an array must have the same type. Array has a fixed length unlike many other programming languages.

example:

1 | |

显式指定数据类型和长度:

1 | |

生成相同元素:

1 | |

访问

1 | |

Rust 会出现runtime panic,当你访问无效内存时,此时程序自动退出。

函数

Rust code uses snake case as the conventional style for function and variable names.

For example,

1 | |

Rust doesn’t care where you define your functions, only that they’re defined somewhere.

函数参数

1 | |

Function Bodies Contain Statements and Expressions

Statements: instructions that perform some action and do not return a value.Expressions: evaluate to a resulting value.

Calling a macro, Block are both expressions.

1 | |

the line (x+1) without semicolon at the end determine the value of entire block. In this case, value of x+1 is passed to y.

Functions with return values.

1 | |

Comments

使用//

Control Flow

if Expression

1 | |

condition 必须是 bool 值

use if in let statements

if是 expression,所以可以这么写:

1 | |

loops

三种循环:

loopwhilefor

Repeating with loop

重复循环

1 | |

从循环中返回值:

1 | |

break关键字用于指定返回值

Conditional Loops with while

1 | |

Looping through a collection with for

1 | |

Range: a type provided by the standard library that generates all numbers in sequence starting from one number and ending before another number.

1 | |

4. Ownership

What is ownership

Stack and Heap

Stack:

- stores data that must have a known, fixed size.

- new data is alwaysat the top of the stack, thus the access is faster

Heap:

- stores data with an unknown size at compile time or size might change.

- is less organized

- is slower. Data is access through pointer.

Ownership rules

- Each value in Rust has a variable that’s called its owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Variable Scope

A scope is the range within a program for which an item is valid.

1 | |

String type

The value of string literals are hardcoded into the program. (immutable)

The string type is allocated on the heap.

1 | |

:: is an operator that allows us to namespace this particular from function under the String type.

Rust don’t have a GC. The memory is automatically returned once the variable that owns it goes out of scope.

Ways variables and data interact: Move

1 | |

In this case, only pointer is copied. The content of s1 is not copied. (like shallow copy)

This is a problem: when s2 and s1 go out of scope, they will both try to free the same memory. This is known as a double free error and is one of the memory safety bugs we mentioned previously and it can potentially lead to security vulnerabilities.

In this situation in Rust, s1 is considered to no longer be valid and is invalidated by Rust. Instead of being called a shallow copy, it’s known as a move.

In addition, there’s a design choice that’s implied by this: Rust will never automatically create “deep” copies of your data. Therefore, any automatic copying can be assumed to be inexpensive in terms of runtime performance.

Ways variables and data interact: Clone

to deeply copy the heap data,

1 | |

some arbitrary code is being executed and that code may be expensive.

Stack-only data: copy

Copies of the actual values are quick to make. So, there’s no difference between deep and shallow copying in this situation.

Rust has a special annotation called the

Copytrait that we can place on types like integers that are stored on the stack.If a type implements the

Copytrait, an older variable is still usable after assignment.Rust won’t let us annotate a type with the

Copytrait if the type, or any of its parts, has implemented theDroptrait.

Types that implement Copy:

- All Integer types

- The Boolean type

- All the floating point types

- The character type

- Tuples, if they only contain types that also implement Copy

Ownership and Functions

Example shows variables go into and out of scope.

1 | |

Return Values and Scope

Returning values can also transfer ownership.

The ownership of a variable follows the same pattern every time: assigning a value to another variable moves it. When a variable that includes data on the heap goes out of scope, the value will be cleaned up by drop unless the data has been moved to be owned by another variable.

==return multiple values==

1 | |

Intreseting things:

When I want to simplify the

cal_len:

2

3fn cal_len(s: String) -> (String, usize) {

(s, s.len())

}I get:

borrow of moved value: `s`which means the

sgave the ownership to s2 in main()

References and Borrowing

using reference:

1 | |

Note:

The opposite of referencing by using

&is dereferencing, which is accomplished with the dereference operator,*.

Mutable References

1 | |

==restriction==

1> you can have only one mutable reference to a particular piece of data in a particular scope. This code will fail:

1 | |

2> We also cannot have a mutable reference while we have an immutable one. Users of an immutable reference don’t expect the values to suddenly change out from under them!

The benefit of having this restriction is that Rust can prevent data races at compile time. A data race is similar to a race condition and happens when these three behaviors occur:

- Two or more pointers access the same data at the same time.

- At least one of the pointers is being used to write to the data.

- There’s no mechanism being used to synchronize access to the data.

Reference’s scope starts from where it is introduced and continues through the last time that reference is used.

1 | |

These scopes don’t overlap, so this code is allowed.

Dangling References

in c++:

1 | |

p is called a dangling pointer

example of dangling reference in Rust:

1 | |

Rules of References

- At any given time, you can have either one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.

- References must always be valid.

The Slice Type

Another data type that does not have ownership is the slice

Slices let you reference a contiguous sequence of elements in a collection rather than the whole collection.

Here comes a small problem:

find the first word in string.

1 | |

String Slices

A string slice is a reference to part of a string.

Use [starting_index..ending_index] to create a string slice. The length is ending_idx-starting_idx.

For example,

1 | |

String slice range indices must occur at valid UTF-8 character boundaries. If you attempt to create a string slice in the middle of a multibyte character, your program will exit with an error. For the purposes of introducing string slices, we are assuming ASCII only in this section; a more thorough discussion of UTF-8 handling is in the “Storing UTF-8 Encoded Text with Strings” section of Chapter 8.

The type that signified “string slice” is written as &str

1 | |

看似天衣无缝的代码,运行结果仍然符合马克思主义基本原理的特点。矛盾的同一性和斗争性体现在了:

1 | |

s.clear() need to get a mutable reference to truncate the String. (Rust disallows this)

这带给我们的启发是,事物是普遍联系和永恒发展的,其中对s.clear的矛盾分析方法同时也是马克思主义的世界观和方法论。是s.clear的客观存在决定了我们的意识。同时s.clear也是我们主观意识的客观反应即不同的人对于这个客观存在的反应可能是不同的。这其实也告诉了我们,物质是能为人类所反映的客观存在。

String Literals Are Slices

String literals are stored inside the binary, and it’s also immutable for &str is an immutable reference.

String Slices as Parameters

signature of previous function.

string literals are slices so use slices instead.

It can make our API more general and useful without losing any functionality.

1 | |

Other Slices

There is a more general slice type.

1 | |

the type of slice is &[i32]

Summary

The concepts of ownership, borrowing, and slices ensure memory safety in Rust programs at compile time.

5. Struct

Defining and Instantiating Structs

Struct have corresponding name in each field.

Defining a struct :

1 | |

if we use mut, every field of struct must be mutable.

Returns a User

1 | |

Field Init Shorthand when Variables and Fields Have the Same Name

field init shorthand

1 | |

Creating Instances From Other Instances

Struct Update Syntax

1 | |

—> to use less code:

1 | |

.. specifies that the remaining fields not explicitly set should have the same value as the fields in the given instance.

Using Tuple Structs without Named Fields to Create Different Types

tuple struct : have name provides but don’t have names associated with their fields.

1 | |

Unit-Like Structs

A unit-like struct is a struct that don’t have any fields, behave similarly to (), the unit type.

Unit-like struct can be useful in situations in which you need to implement a trait on some type but don’t have any data that you want to store in the type itself.

Method Syntax

Defining methods

Example:

1 | |

If we need to modify the filed in struct, use &mut self as parameter instead.

Automatic referencing and dereferencing

When you call a method with

object.some_method(), Rust automatically adds in&,&mut, or*so object matches the signature ofthe method. In other words, the following are the same:

2foo.bar(&p);

(&foo).bar(&p);

with more parameters

1 | |

Associated Functions

A function without parameter self is called associated function

for example,

1 | |

:: is used for both associated functions and namspaces created by modules.

6. Enums and Pattern Matching

Defining an Enum

We can enumerate all possible variants, which is where enumeration gets its name.

1 | |

Enum Values

1 | |

We can represent the same concept in a more concise way using just an enum, rather than an enum inside a struct, by putting data directly into each enum variant.

1 | |

There’s another advantage to using an enum rather than a struct: each variant can have different types and amounts of associated data.

Example:

1 | |

Quithas no data associated with it at all.Moveincludes an anonymous struct inside it.Writeincludes a singleString.ChangeColorincludes threei32values.

Define Method on Enum:

1 | |

==?怎样知道调用call方法的是哪一个enum值?==

The Option Enum

Rust does not have nulls, but it does have an enum that can encode the concept of a value being present or absent. This enum is Option<T>, and it is defined by the standard library as follows:

1 | |

In order to have a value that can possibly be null, you must explicitly opt in by making the type of that value Option<T>. Then, when you use that value, you are required to explicitly handle the case when the value is null.

Everywhere that a value has a type that isn’t an Option<T>, you can safely assume that the value isn’t null. This was a deliberate design decision for Rust to limit null’s pervasiveness and increase the safety of Rust code.

The match Control Flow operator

Think of a

matchexpression as being like a coin-sorting machine: coins slide down a track with variously sized holes along it, and each coin falls through the first hole it encounters that it fits into. In the same way, values go through each pattern in amatch, and at the first pattern the value “fits,” the value falls into the associated code block to be used during execution.

I think match expression like switch-case in cpp, but the match expression returns some value while switch doesn’t.

Example of coin-sorting machine:

1 | |

1 | |

Matching with Option<T>

Suppose we want to write a function that takes an Option<i32> as parameter. If there’s a value inside, adds 1 to that.

1 | |

In Rust, matches are exhaustive: we must exhaust every last possibility in order for the code to be valid. It protects us from assuming that we have a value when we might have null.

The _ Placeholder

Suppose we only care about these values: 1,3 and we don’t want to list out all other values.

we can use the special pattern _ instead:

1 | |

Concise Control Flow with if let

If we want to handle values that match one pattern while ignoring the rest, we can use if let.

1 | |

print the sentence if and only if my ultimate percentage get to 100.

Instead, to write this in a shorter way using if let:

1 | |

7. Managing Growing Projects with Packages, Crates, and Modules

==TODO==

8. Common Collections

three commonly used collections:

- vector

- string

- hash map

vector<T>

Create a New Vector

Create an empty vector:

1

let v: Vec<i32> = Vec::new();vec!macro1

let v = vec![1,2,3]; // Vec<i32> type

Updating a Vector

1 | |

Dropping a Vector Drops Its Elements

1 | |

Accessing Elements in Vectors

[]indexing syntax ( returning a reference )getmethod ( returningOption<&T>)

两个mut联想到写覆盖

一个mut 一个immut联想到不可重复读

The borrow checker enforces the ownership and borrowing rules to ensure the reference is valid.

Iterating over the values in a Vector

use for loop to get mutable references to each element in a vector:

1 | |

Using an enum to store multiple types

1 | |

If you don’t know the exhaustive set of types the program will get at runtime to store in a vector, the enum technique won’t work. Instead, you can use a trait object.

Strings (storing UTF-8 encoded text)

Both String and string slices are stored in UTF-8

Other string types in standard library:0sString, 0sStr, CString, Cstr

string literals to String:

1 | |

Appending to a String with push_str and push

push_strto append string slice( literals are string slice )pushappend single character

Concatenation with + or format! macro

1 | |

The reason why s1 is moved:

+ operator use add method, whose signature looks like:

1 | |

But

&s2is the type&Stringandaddfunction takes&stras param. Why?Rust uses a deref coercion which turns

&s2intos2[..]

format! macro:

1 | |

Indexing into Strings

String is wrapped over Vec<u8>, so indexing syntax gets bytes slice.

如果尝试使用形如s[0]的索引,其表示的含义是字节数组里面的第一个元素。

而Rust 使用的是Unicode,unicode是变长编码,中文的binary开头是1110,所以是3byte,英文是0开头,这也解释了为什么”卢bw”的len是5。

code:

2

3

4

5println!("{}","卢bw".to_string().len());

let s1 = "田所";

println!("{:#?}",s1.bytes()); // get byte array

let byte_arr = vec![97];

println!("{:#?}",String::from_utf8(byte_arr).unwrap()); // print a

Iterating over String

(Note that this string begins with the capital Cyrillic letter Ze)

1 | |

Hash Maps

Hash Maps is used to store keys with associated values.

Create a new Hash Map

HashMap is not included in the features brought into scope automatically in the prelude.

Like vectors, hash maps are homogeneous: all of the keys must have the same type, and all of the values must have the same type.

1 | |

Another way to create a HashMap is using iterators and the collect method on a vector of tuple.

1 | |

we use underscores as placeholder because Rust can infer both data types.

HashMap and Ownership

or types that implement the Copy trait, like i32, the values are copied into the hash map. For owned values like String, the values will be moved and the hash map will be the owner of those values.

1 | |

If we insert references to values into the hash map, the values won’t be moved into the hash map. The values that the references point to must be valid for at least as long as the hash map is valid. We’ll talk more about these issues in the “Validating References with Lifetimes” section in Chapter 10.

Accessing values in Hash Map

getmethod:

1 | |

forloop

1 | |

This code will print each pair in an ==arbitrary== order:

Updating a Hash Map

Overwrite

If you insert twice, the former value will be overwritten because the hash map can only contain one KV pair.

Insert a value only if the key has no value

entry() returns an enum called Entry

1 | |

1 | |

Updating a value based on the old value

1 | |

or_insert() returns a mutable reference (&mut V) to the value for this key.

So we should dereference count using the asterisk

9. Error Handling

Unrecoverable Errors with panic!

When panic! macro executes, the program will print a failure message, unwind and clean up the stack, and then quit.

Unwinding the Stack or Aborting in Response to a Panic

By default, when a panic occurs, the program starts unwinding, which means Rust walks back up the stack and cleans up the data from each function it encounters. But this walking back and cleanup is a lot of work. The alternative is to immediately abort, which ends the program without cleaning up. Memory that the program was using will then need to be cleaned up by the operating system.

in Cargo.toml:

2[profile.release]

panic = 'abort'

Using a panic! backtrace

Setting the environment variable RUST_BACKTRACE to get a backtrace of exactly what happened to cause the error.

A backtrace is a list of all the functions that have been called to get to this point. The key to reading the backtrace is to start from the top and read until you see files you wrote. That’s the spot where the problem originated. The lines above the lines mentioning your files are code that your code called; the lines below are code that called your code.

1 | |

In order to get backtraces with this information, debug symbols must be enabled. Debug symbols are enabled by default when using cargo build or cargo run without the --release flag, as we have here.

Recoverable Errors with Result

Result enum is defined as having two variants, Ok and Err

1 | |

Example: opening a file

1 | |

The return type of the File::open function is a Result<T, E>.

The generic parameter T has been filled in here with the type of the success value, std::fs::File, which is a file handle. The type of E used in the error value is std::io::Error.

Matching on differenct errors

1 | |

A more seasoned Rustacean might write this code:

1 | |

Shortcuts for Panic on Error: unwrap and expect

Result<T,T> type has many helper methods.

unwrap() is a shortcut method implemented like match expression.

- If

Resultvalue isOkvariant,unwrapwill return the value insideOk - If the value is

Errvariant, it will call thepanic!macro for us.

1 | |

Another method, expect, which is similar to unwrap, lets us choose the panic! error message.

Using expect instead of unwrap and providing good error messages can convey your intent and make tracking down the source of a panic easier:

1 | |

Propagating Error

When you’re writing a function whose implementation calls something that might fail, instead of handling the error within this function, you can return the error to the calling code so that it can decide what to do. This is known as propagating the error. The calling code might have more information or logic that dictates how the error should be handled than what you have available in the context of your code.

1 | |

A shortcut for propagating errors: ? Operator

1 | |

There’s a way to make this even shorter:

1 | |

? operator can be used in funcitons that return Result

? operator can be only used in a function that return Result or Option or another type that implements std::ops::Try

The main() function is special, and there are restrictions on what its return type must be.

Apart from (), another valid return type is Result<T, E>:

1 | |

The Box<dyn Error> type is called a trait object.

To panic! or not to panic!

==That is a question==

10. Generic Types, Traits and Lifetimes

Generic Data Types

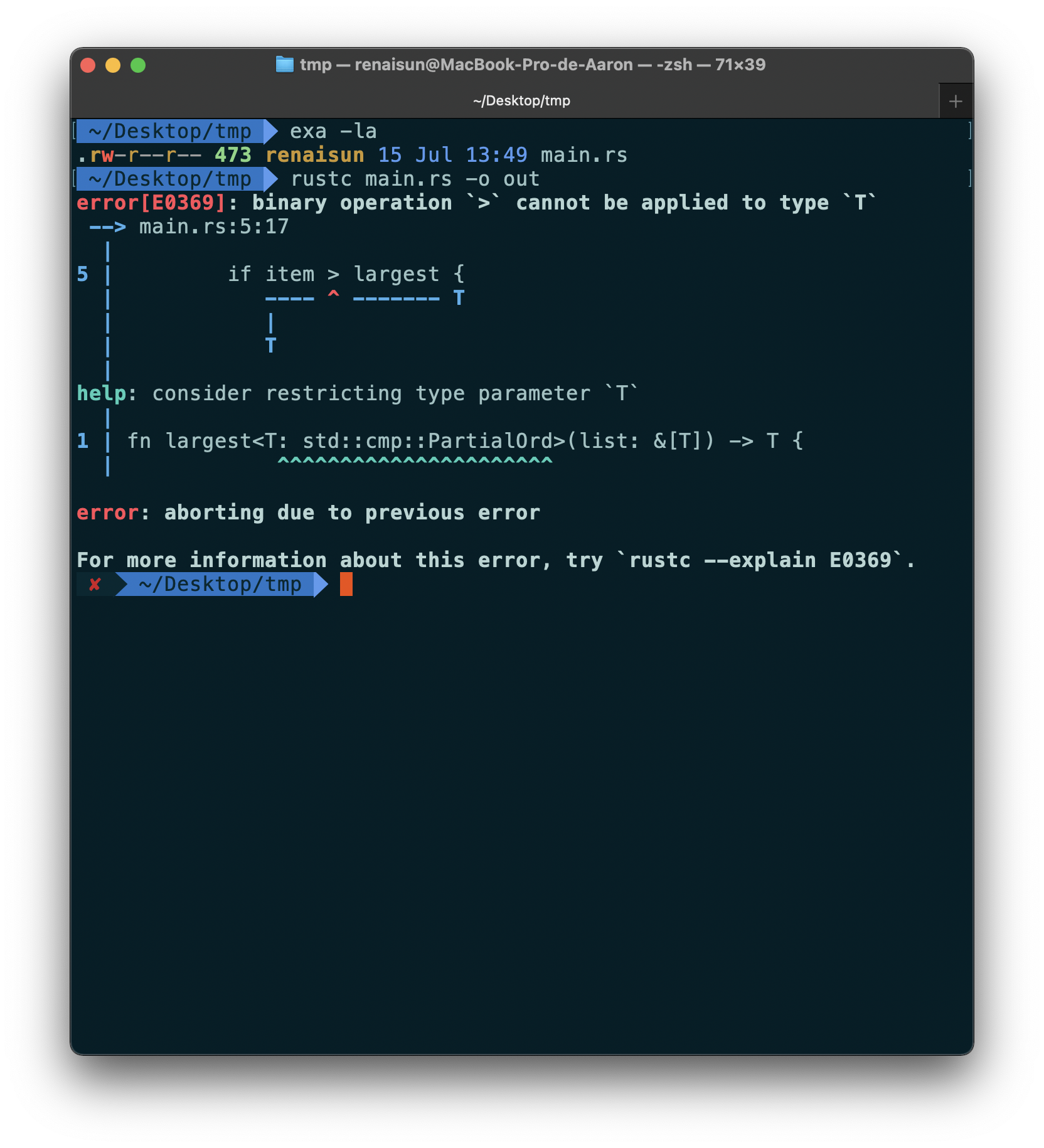

In function definitions

1 | |

Will get the error:

std::cmp::PartialOrd is a trait.

For now, this error states that the body of largest won’t work for all possible types that T would be.

To enable comparisons, the standard library has the std::cmp::PartialOrd trait that you can implement on types.

In struct definitions

To define a Point Struct where x and y both generics but could have different types, we can use multiple generic type parameters.

1 | |

You can use as many generic type parameters in a definition as you want, but using more than a few makes your code hard to read. When you need lots of generic types in your code, it could indicate that your code needs restructuring into smaller pieces.

In enum definitions

Option<T> and Result<T,E> , provided by the standard library , are enums that hold generic data types.

1 | |

When you recognize situations in your code with multiple struct or enum definitions that differ only in the types of the values they hold, you can avoid duplication by using generic types instead.

In method definitions

1 | |

method x returns the reference to &self.x.

Declaring T after impl makes compiler know T is a generic type but not a concrete type.

Also, we can only implement methods only on Point<f32> instances rather than on Point<T> instances with any generic type.

1 | |

Generic type parameters in a struct definition aren’t always the same as those you use in that struct’s method signatures. For example,

1 | |

The purpose of this example is to demonstrate a situation in which some generic parameters are declared with impl and some are declared with the method definition. Here, the generic parameters T and U are declared after impl, because they go with the struct definition. The generic parameters V and W are declared after fn mixup, because they’re only relevant to the method.

Performance of code using generics

The good news is that Rust implements generics in such a way that your code doesn’t run any slower using generic types than it would with concrete types.

Rust accomplishes this by performing ==monomorphization== of the code that is using generics at compile time. Monomorphization is the process of turning generic code into specific code by filling in the concrete types that are used when compiled.

Trait: defining shared behaviour

A trait tells the Rust compiler about functionality a particular type has and can share with other types.

We can use trait bounds to specify that a generic can be any type that has certain behavior.

Trait is similar to interface in Java, virtual function in C++?

Defining a trait

A type’s behavior consists of the methods we can call on that type. Different types share the same behavior if we can call the same methods on all of those types. Trait definitions are a way to group method signatures together to define a set of behaviors necessary to accomplish some purpose.

Suppose we want to make a media aggregator library that can display summaries of data.

1 | |

Each type implementing this trait must provide its own custom behavior for the body of the method. The compiler will enforce that any type that has the Summary trait will have the method summarize defined with this signature exactly.

Implementing a trait on a type

1 | |

impl {trait_name} for {type_name} {}

We can’t implement external traits on external types. For example, we can’t implement the

Displaytrait onVec<T>within ouraggregatorcrate, becauseDisplayandVec<T>are defined in the standard library and aren’t local to ouraggregatorcrate. This restriction is part of a property of programs called coherence, and more specifically the orphan rule, so named because the parent type is not present. This rule ensures that other people’s code can’t break your code and vice versa. Without the rule, two crates could implement the same trait for the same type, and Rust wouldn’t know which implementation to use.

Default implementations

Having default behavior for some methods in a trait instead of requiring implementations for thoes methods on every type is useful sometimes.

For example, specify default string for summerize method:

1 | |

Traits as parameters

In order to define a function that takes parameters which implement specified trait, we can use impl Trait syntax:

1 | |

Trait bound syntax

The impl Trait syntax works for straightforward cases but is actually syntactic sugar for a longer form.

1 | |

For example, the trait bound syntax helps simplify:

1 | |

Into ….—>

1 | |

Specifying multiple trait bounds wtih the + syntax

We specify in the notify definition that item must implement both Display andSummary. We can do so using the + syntax:

1 | |

The + syntax is also valid with trait bounds on generic types:

1 | |

Clearer trait bounds with where clauses

Using too many trait bounds has its downsides:

1 | |

Instead, we can use a where clause:

1 | |

Returning types that implement traits

use the impl Trait syntax in the return position to return a value of some type that implements a trait:

1 | |

By using impl Summary, we can specify that the type of return value implement the Summary trait without naming the concrete type.

The ability to return a type that is only specified by the trait it implements is especially useful in the context of closures and iterators.

==WHY?==

However, you can only use

impl Traitif you’re returning a single type. For example, this code that returns either aNewsArticleor aTweetwith the return type specified asimpl Summarywouldn’t work:

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}, by {} ({})", self.headline, self.author, self.location)

}

}

pub struct Tweet {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub retweet: bool,

}

impl Summary for Tweet {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}: {}", self.username, self.content)

}

}

fn returns_summarizable(switch: bool) -> impl Summary {

if switch {

NewsArticle {

headline: String::from(

"Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!",

),

location: String::from("Pittsburgh, PA, USA"),

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from(

"The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best \

hockey team in the NHL.",

),

}

} else {

Tweet {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from(

"of course, as you probably already know, people",

),

reply: false,

retweet: false,

}

}

}Returning either a

NewsArticleor aTweetisn’t allowed due to restrictions around how theimpl Traitsyntax is implemented in the compiler.“Using Trait Objects That Allow for Values of Different Types”

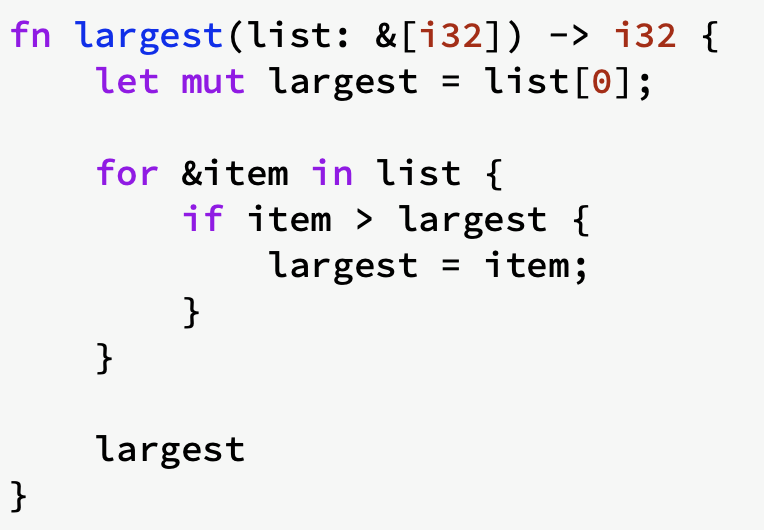

Example: Fixing the largest function with trait bounds

First, limit to the types which implements

std::cmp::PartialOrd1

2fn largest<T: PartialOrd>(list: &[T]) -> T {

// &[T] means the reference to list which stores the type of TNext, to call this code with only those types that implement the

Copytrait.Line1 copy the value of list[0] to largest. So

Tshould implements Copy trait.

Code snippet in DOCS

1 | |

This version didn’t use Copy traits. However, if using reference, those type which don’t implement Copy can be passed to largest function

1 | |

Using traits bounds to conditionally implement methods

Conditionally implement methods on a generic type depending on trait bounds :

1 | |

Implementations of a trait on any type that satisfies the trait bounds are called blanket implementations.

==means

ToStringis automatically implemented????==The standard library implements the

ToStringtrait on any type that implements theDisplaytrait. Theimplblock in the standard library looks similar to this code:

2

3impl<T: Display> ToString for T {

// --snip--

}

Validating references with lifetimes

Every reference in Rust has a lifetime, which is the scope for which that reference is valid. Rust requires us to annotate the relationships using generic lifetime parameters to ensure the actual references used at runtime will definitely be valid.

Preventing dangling references with lifetimes

1 | |

An attempt to use a reference whose value has gone out of scope

The Rust compiler has a ==borrow checker== that compares scopes to determine whether all borrows are valid.

Generic lifetimes in functions

Assume we want to write a function that returns the longer of two string slices:

1 | |

If we try to implement the funciton like this, it won’t compile:

1 | |

The reason is that the borrow checker cannot verity whether the reference we return will always be valid.

To fix this, we need to add generic lifetime parameters that define the relationship between the references for the borrow checker to perform its analysis.

Lifetime annotation syntax

Lifetime annotations describe the relationships of the lifetimes of multiple references to each other without affecting the lifetimes.

1 | |

modified function:

1 | |

'a reveals that the function signature also tells Rust that the string slice returned from the function will live at least as long as lifetime 'a. In practice, it means that the lifetime of the reference returned by thelongest function is the same as the smaller of the lifetimes of the references passed in.

Lifetime annotations in struct definitions

1 | |

the struct with a lifetime annotation guarantee the reference to string slice part is always vaild until the novel goes out of the scope.

Lifetime Elision

If Rust deterministically applies the rules but there is still ambiguity as to what lifetimes the references have, the compiler won’t guess what the lifetime of the remaining references should be and give a compile error.

Lifetimes on function or method parameters are called input lifetimes, and lifetimes on return values are called output lifetimes.

Rules:

- each parameter that is a reference gets its own lifetime parameter.

- if there is exactly one input lifetime parameter, that lifetime is assigned to all output lifetime parameters

- if there are multiple input lifetime parameters, but one of them is

&selfor&mut selfbecause this is a method, the lifetime ofselfis assigned to all output lifetime parameters.

Lifetime annotations in method definitions

1 | |

The static lifetime

'static means this reference can live for the entire duration of the program.

Generic Type Parameters, Trait Bounds, and Lifetimes Together

1 | |

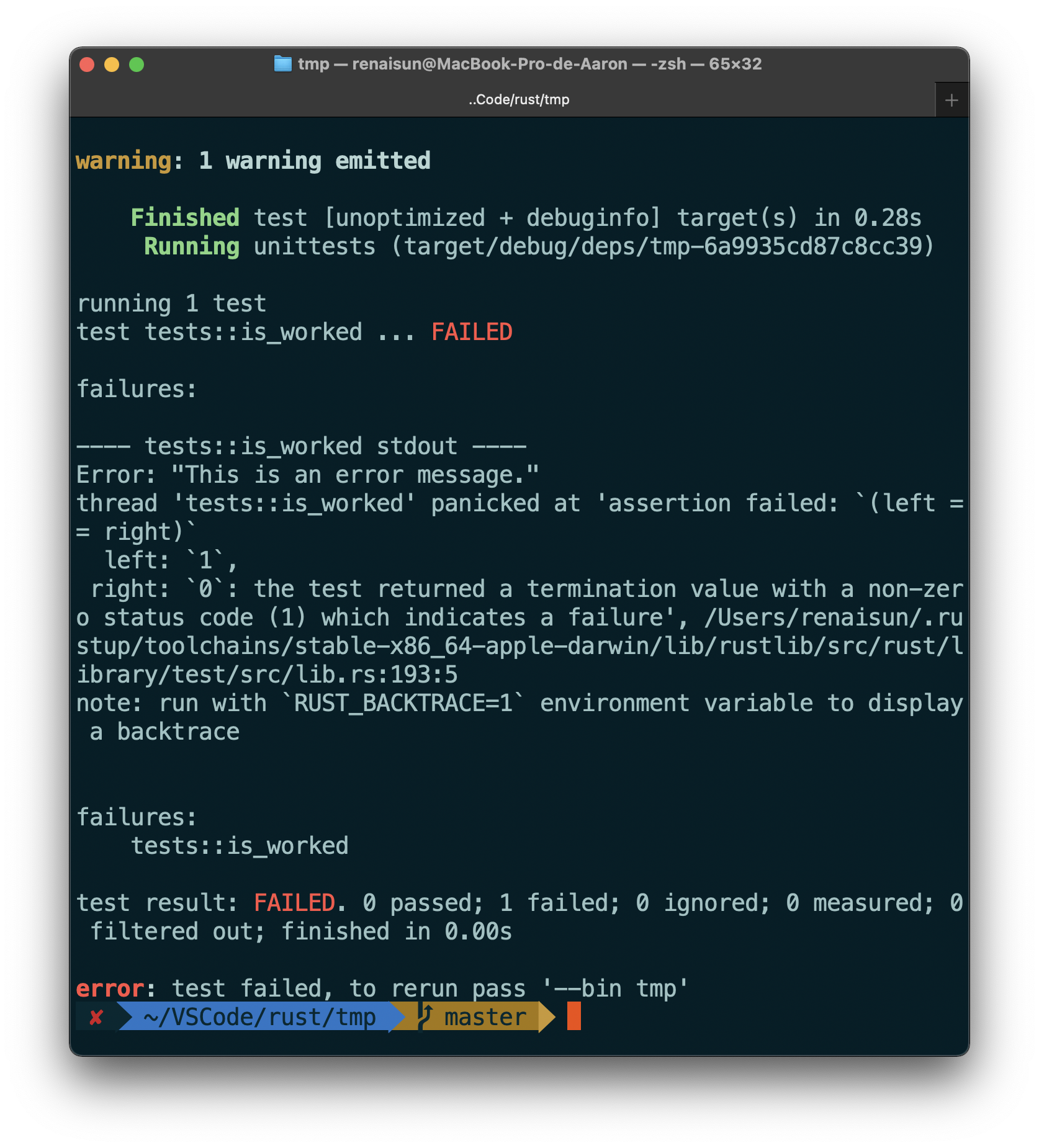

Writing automated tests

How to write tests

steps to perform test:

- set up needed data or state

- run the code you want to test

- assert the result are what you expect

The anatomy of a test function

a test is a function that annotated with the test attribute.

Attributes are metadata about pieces of Rust code;

When you run tests with cargo test, Rust builds a test runner binary that runs the functions annotated with the test attribute.

assert! macro

If the value given to assergt is false, it calls panic!

assert_eq! and assert_ne!

assert_eq!callspanic!when two values given are NOT equal-

assert_ne!callspanic!when two values given are NOT equal

Adding custom failure massages

1 | |

Check for panics with should_panic

1 | |

by adding another attribute, should_panic, to our test function, this attribute makes a test pass if the code inside the function panics; the test will fail if the code inside the function doesn’t panic.

expected parameter

The test harness will make sure that the failure message contains the provided text.

1 | |

Using Result<T, E> in tests

1 | |

Controlling how tests are run

cargo test --helpdisplays the options you can use withcargo testcargo test -- --helpdisplays the options you can use after the separator--.

Run tests in parallel or consecutively

1 | |

to tell the program not to use any parallelism.

Showing function output

1 | |

Runing a subset of tests by name

name or names of the test(s) can be passed which you want to run as argument.

In program:

1 | |

to run single tests:

1

cargo test one_hundredto run multiple tests:

1

cargo test addis to run all test with

addin the name.

Ignore tests unless specifically requested

1 | |

To run ignored tests:

1 | |

Test organization

- unit tests : testing one module in isolation at a time

- integration tests : are entirely external to your library and use your code in the same way any other external code would, using only the public interface and potentially exercising multiple modules per test.

Unit tests

The #[cfg(test)] annotation on the tests module tells Rust to compile and run the test code only when you run cargo test, not when you run cargo build. This saves compile time when you only want to build the library and saves space in the resulting compiled artifact because the tests are not included.

This includes any helper functions that might be within this module, in addition to the functions annotated with #[test].

Testing private functions

A privated function can be tested in test module.

Integration Tests

Integration Tests:

- external to your library

- only call functions in your library’s public API

To create integration tests, we need a tests directory

The tests directory

- next to

src - each of the file in this directory are compiled as an indificual crate

TODO

https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch11-03-test-organization.html

An I/O project building a command line program

Accept CLI arguments

Fetch arguments and put them into Vector:

1 | |

In this case, type annotation is neccessary for compiler to decide the kind of collection we want.

Reading a file

1 | |

Deal with error

unwrap_or_else

used to define some custom, non-panic! Error handling. If the value of Result is:

Ok: the inner value of Ok will be returnedErr: will call the code in the closure, which is an anonymouss function defined and passed as an argument to unwrap_or_else

process::exit

stop the program immediately and return the number that was passed as the exit status code.

Box<dyn Error>

It is a kind of trait object returned by function. Inside the function body, we will return a type that implements the Error trait, but we don’t need to specify the particular type of return value.

env::var()

returns a Result

- is

Okvariant containing the value of the environment variable if it is set. - is

Errvariant otherwise

eprintln!()

Print error to stderr

Functional Language Features: Iterators and Closures

Closures

Closures in Rust are anonymous functions you can save in a variable or pass a s arguments to other functions.

Refactoring with closures to store code

1 | |

Closure type inference and annotation

If we want to increase explicitness and clarity at the cost of being more verbose than strictly necessary.

annotating the types:

1 | |

Attempting to call a closure whose types are inferred with two different types will cause an error.

Storing closures using generic parameters and the Fn traits

memoization or lazy evaluatioin: create a struct that will hold the closure and the resulting value of calling the closure. The struct will execute the closure only if we need the resulting value, and it will cache the resulting value for reuse.

Each closure instance should have its own unique anonymous type: even if two closures have the same signature, their types are still considered different.

All closures implement at least one of the traits: Fn, FnMut, or FnOnce.

Example

We add types to the Fn trait bound to represent the types of the parameters and return values the closures must have to match this trait bound.

1 | |

Limitations of the Cacher implementation

1 | |

the test will fail because then 1 is given to c, Some(1) will be saved and always be returned.

However, we can modify Cacher to hold a hashmap rather than a single value.

Caputuring the environment with closures

Closures can capture values from their environment in three ways, which directly map to the three ways a function can take a parameter: taking ownership, borrowing mutably, and borrowing immutably. These are encoded in the three Fn traits as follows:

FnOnceconsumes the variables it captures from its enclosing scope, known as the closure’s environment. To consume the captured variables, the closure must take ownership of these variables and move them into the closure when it is defined. TheOncepart of the name represents the fact that the closure can’t take ownership of the same variables more than once, so it can be called only once.FnMutcan change the environment because it mutably borrows values.Fnborrows values from the environment immutably.

moveclosures example

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11fn main() {

let x = vec![1, 2, 3];

let equal_to_x = move |z| z == x;

println!("can't use x here: {:?}", x);

let y = vec![1, 2, 3];

assert!(equal_to_x(y));

}Note:

moveclosures may still implementFnorFnMut, even though they capture variables by move.This is because the traits implemented by a closure type are determined by what the closure does with captured values, NOT how it captures them. The

movekeyword only specifies the latter.

Processing a series of items with Iterators

In Rust, iterators are lazy, meaning they have no effect until you call methods that consume the iterator to use it up.

Iterator trait and the next method

All iterators implement a trait named Iterator that is defined in the standard library.

Def looks like:

1 | |

type Item and Self::Item define an associated type.(Item type will be the type returned from the iterator)

We didn’t need to make v1_iter mutable when we used a for loop because the loop took ownership of v1_iter and made it mutable behind the scenes.

Note:

- the values we get from the calls to

nextare immutable references to the values in the vector. - call

into_iterinstead ofiterto create an iterator that takes ownership ofv1and returns owned values. - call

iter_mutinstead ofiterto get mutable references.

Methods that consume the iterator

Methods that call next are called consuming adaptors, because calling them uses up the iterator.

One example is the sum method.

1 | |

We aren’t allowed to use v1_iter after the call to sum because sum takes ownership of the iterator we call it on.

Methods that produce other iterators

iterator adaptors allow you to change iterators into different kinds of iterators.

1 | |

This is a great example of how closures let you customize some behavior while reusing the iteration behavior that the Iterator trait provides.

Using closures that capture their environment

The filtermethod on an iterator takes a closure that takes each item from the iterator and returns a Boolean.

- If the closure returns

true, the value will be included in the iterator produced byfilter. - If the closure returns

false, the value won’t be included in the resulting iterator.

Example

1 | |

Mention: the vector of shoes is moved to in_my_size

Creating iterators with the Iterator trait

The only definition required for Iterator trait is next method.

Sample of iterator in the range of 1..=5

1 | |

Using other iterator trait method

1 | |

Cargo and Crates.io

Customize build with release profiles

Cargo has two main profiles:

devprofile:cargo buildreleaseprofile:cargo build --release

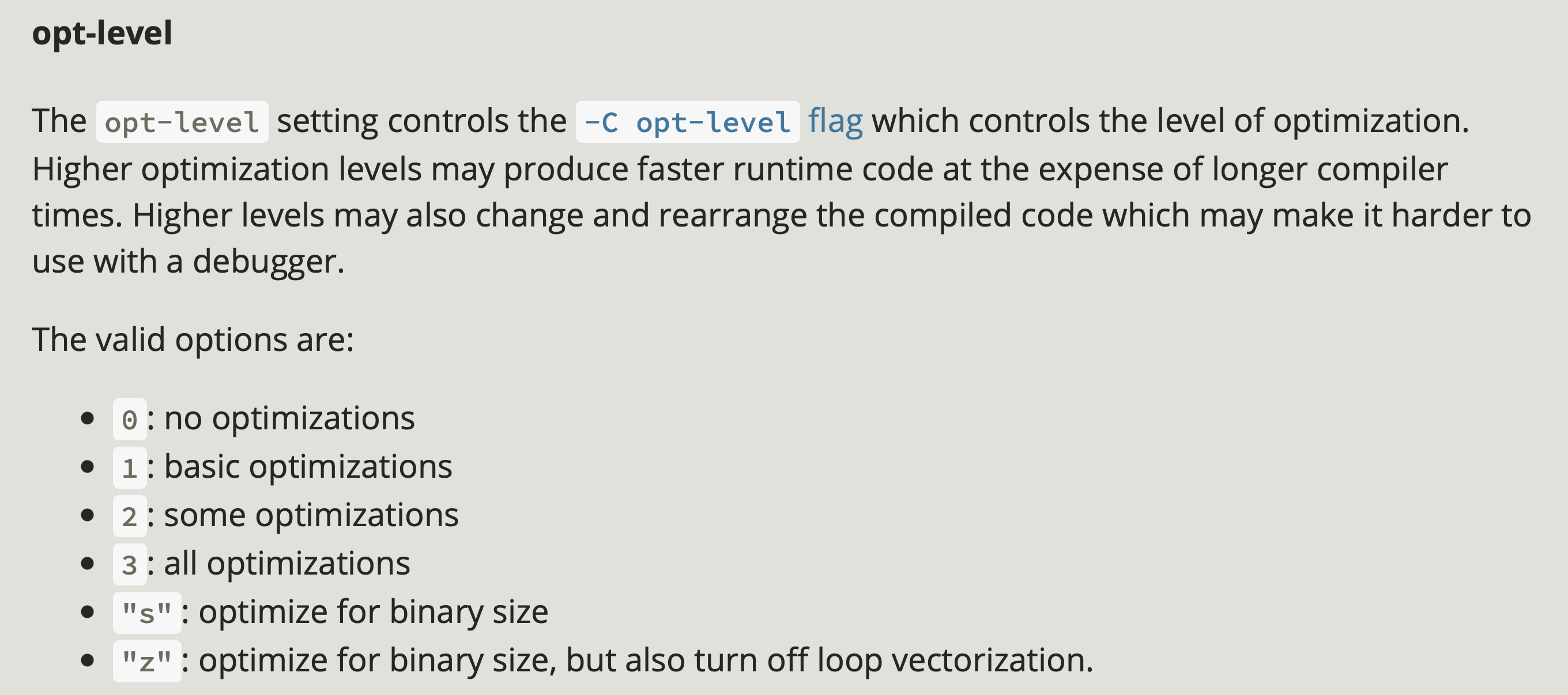

in Cargo.toml we can set opt-level setting

1 | |

Publish a crate to crates.io

// TODO

Cargo workspace

A workspace is a set of packages that share the same Cargo.lock and output directory.

Example

To make a project using workspace which contains a binary and two libraries.(respectively provide add_one and add_two function)

create a new directory used as a workspace

1 | |

create Cargo.toml

1 | |

create library and binary crate

1 | |

add a path dependency

Cargo doesn’t assume that crates in a workspace will depend on each other, so we need to be explicit about the dependency relationships between the crates.

Assume that we want to use add_one function in the adder crate. Open adder/Cargo.toml:

1 | |

Then we can use add_one:

1 | |

run a specific package

1 | |

depend on an external package in a workspace

1 | |