Record of Learning Rust | Part 2 of 2

Smart Pointers

Smart pointers are data structures that not only act like a pointer but also have additional metadata and capabilities.

In Rust, which uses the concept of ownership and borrowing, an additional difference between references and smart pointers is that references are pointers that only borrow data; in contrast, in many cases, smart pointers own the data they point to.

The characteristic that distinguishes a smart pointer from an ordinary struct is that smart pointers implement the Deref and Drop traits:

Dereftraits allows an instance of the smart pointer struct to behave like a references or smart pointers.Droptraits allows you to customize the code that is run when an instance of the smart pointer goes out of scope.

Using Box<T> to Point to Data on the Heap

Boxes allow you to store data on the heap rather than the stack. What remains on the stack is the pointer to the heap data.

Boxes don’t have performance overhead, other than storing their data on the heap instead of on the stack. But they don’t have many extra capabilities either and often used in these situations:

- When you have a type whose size can’t be known at compile time and you want to use a value of that type in a context that requires an exact size

- When you have a large amount of data and you want to transfer ownership but ensure the data won’t be copied when you do so

- When you want to own a value and you care only that it’s a type that implements a particular trait rather than being of a specific type

Use a Box<T> to store data on the heap

use a box to store an i32:

1 | |

Enabling recursive types with boxes

At compile time, Rust needs to know how much space a type takes up. One type whose size can’t be known at compile time is a recursive type, where a value can have as part of itself another value of the same type.

Use Box<T> to get a recursive type with a known size

1 | |

The Box<T> type is a smart pointer because it implements the Deref trait, which allows Box<T> values to be treated like references. When a Box<T> value goes out of scope, the heap data that the box is pointing to is cleaned up as well because of the Drop trait implementation.

Treating smart pointers like regular references with Deref trait

Following the Pointer to the value with the dereference operator

1 | |

Using Box<T> like a reference

1 | |

Define our own smart pointer

In order to dereference and get inner data, we should implement deref method in Deref trait.

1 | |

*a is equal to what Rust run below code behind the scenes:

1 | |

The reason the deref method returns a reference to a value, and that the plain dereference outside the parentheses in *(y.deref()) is still necessary, is the ownership system. If the deref method returned the value directly instead of a reference to the value, the value would be moved out of self. We don’t want to take ownership of the inner value inside MyBox<T> in this case or in most cases where we use the dereference operator.

Implicit Deref coercions with functions and methods

Deref coercion is a convenience that Rust performs on arguments to functions and methods. Deref coercion works only on types that implement the Deref trait. Deref coercion converts such a type into a reference to another type.

When the Deref trait is defined for the types involved, Rust will analyze the types and use Deref::deref as many times as necessary to get a reference to match the parameter’s type.

How Deref coercion interacts with mutability

Rust does deref coercion when it finds types and trait implementations in three cases:

- From

&Tto&UwhenT: Deref<Target=U> - From

&mut Tto&mut UwhenT: DerefMut<Target=U> - From

&mut Tto&UwhenT: Deref<Target=U>Rust does deref coercion when it finds types and trait implementations in three cases:

Running code on cleanup with the Drop trait

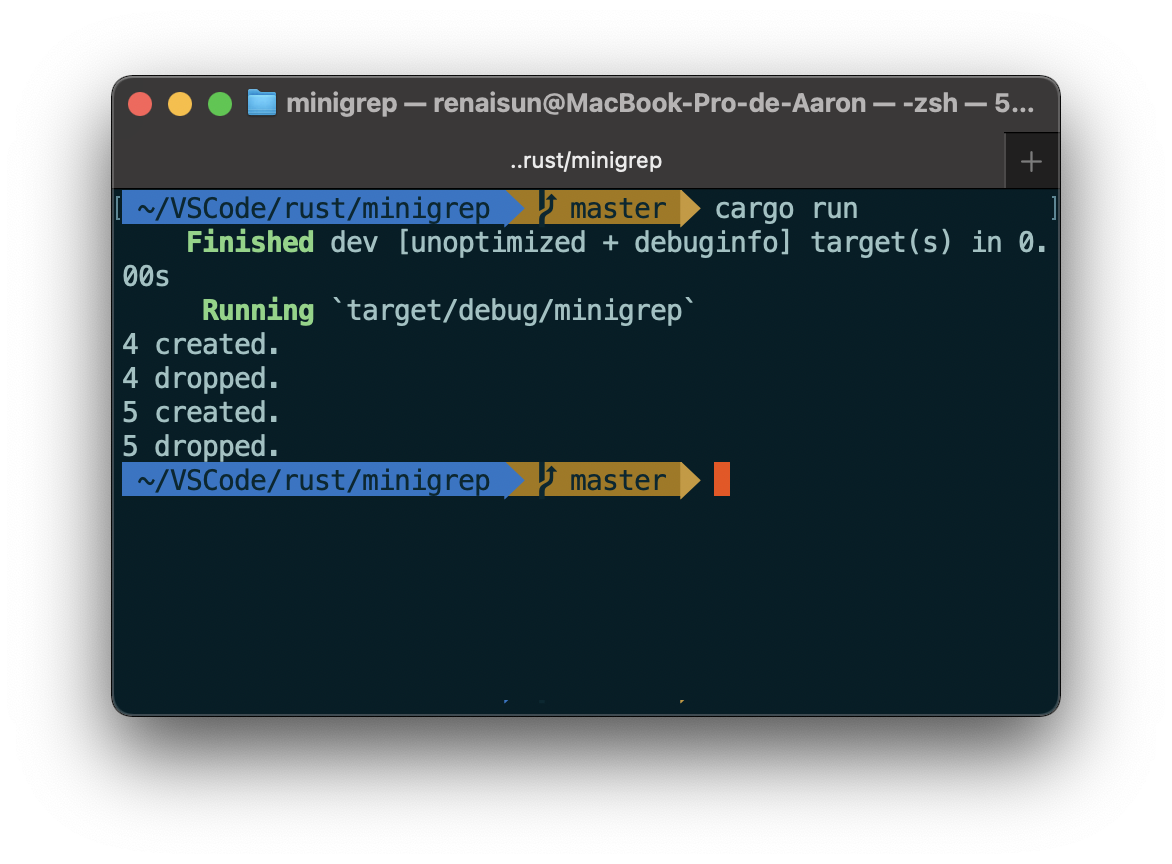

An instance

1 | |

1 | |

and output is:

Note: Drop is included in the prelude.

Drop a value early with std::mem::drop

We’re not allowed to explicitly call drop method which is destructor of the instance. Because it will lead to a double free error.

Instead,

1 | |

Rc<T>, the reference counted smart pointer

Note that Rc<T> is only for use in single-threaded scenarios.

We use the Rc<T> type when we want to allocate some data on the heap for multiple parts of our program to read and we can’t determine at compile time which part will finish using the data last.

Use Rc<T> to share data

For instance:

1 | |

I think the functionality of Rc<T> is revealing the lifetime of variables. In the version of Box<T> implementation, we must change what Box hold to reference and add lifetime annotation to guarantee their value are valid in certain field.

By using Rc::clone for reference counting, we can visually distinguish between the deep-copy kinds of clones and the kinds of clones that increase the reference count.

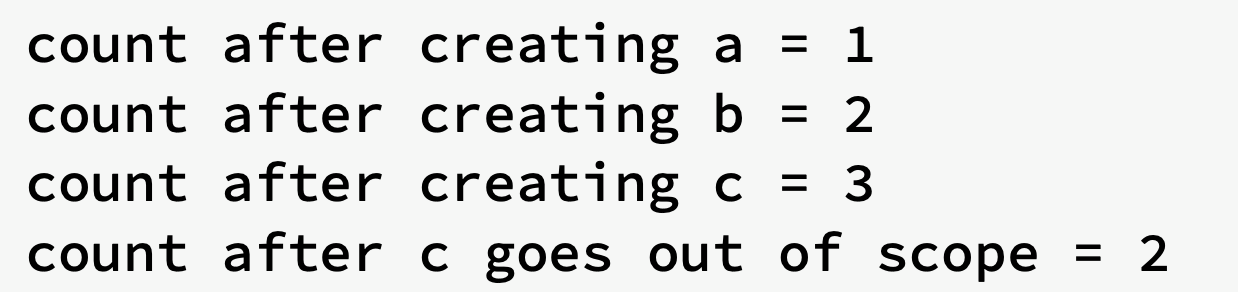

Clone an Rc<T> increases the reference count

strong_count function

1 | |

If Rc<T> allowed you to have multiple mutable references too, you might violate one of the borrowing rules discussed in Chapter 4: multiple mutable borrows to the same place can cause data races and inconsistencies.

RefCell<T> and interior mutability pattern

Interior mutability is a design pattern in Rust that allows you to mutate data even when there are immutable references to that data; normally, this action is disallowed by the borrowing rules.

Enforcing borrowing rules at runtime with RefCell<T>

a recap of reasons to choose …:

Rc<T>enables multiple owners of the same data;Box<T>andRefCell<T>have single owners.Box<T>allows immutable or mutable borrows checked at compile time;Rc<T>allows only immutable borrows checked at compile time;RefCell<T>allows immutable or mutable borrows checked at runtime.- Because

RefCell<T>allows mutable borrows checked at runtime, you can mutate the value inside theRefCell<T>even when theRefCell<T>is immutable.

Interior mutability: a mutable borrow to an immutable value

a value can mutate itself in its methods but appear immutable to other code.

A use case for interior mutability: Mock objects

test double: a general programming concept for a type used in place of another type during testing.

mock objects: specific types of test doubles that record what happens during a test so you can assert that the correct actions took place.

Example

Imagine we have a library used to keep track of a user’s quota for the number of API calls they’re allowed to make.

One of the function we should implement is to notify the user through sending message. Thus:

1 | |

Assume that we want to store the message into a queue which is wating be dealt with:

1 | |

and thats the question, we cannot borrow the object as mutable.

Solution:

store Vec<String> into RefCell<T>

1 | |

then we can implement send method like this:

1 | |

finnally we achieve to get mutable reference from immuable object.

Keep track of borrows at runtime with RefCell<T>

RefCell<T> have borrow and borrow_mut methods:

borrowreturns the smart pointer typeRef<T>borrow_mutreturns the smart pointer typeRefMut<T>

1 | |

the code will compile without any error, but when it runs at test, it will cause a panic with the message “already borrowed: BorrowMutError”.

Having multiple owners of mutable data by combining Rc<T> and RefCell<T>

1 | |

The whole thing is shared and each shared owner gets to mutate the contents. The effect of mutating the contents will be seen by all of the shared owners of the outer Rc because the inner data is shared.

also,

rust - What is the difference between Rc<RefCell

> and RefCell<Rc >? - Stack Overflow

The runtime checks of the borrowing rules protect us from data races, and it’s sometimes worth trading a bit of speed for this flexibility in our data structures.

Also in standard library:

-

Cell<T>the value is copied in and out Mutex<T>offers thread-safe interior mutability

Reference cycles can leak memory

Instance

// TODO

https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch15-06-reference-cycles.html

Preventing reference cycles: turning an Rc<T> into a Weak<T>

You can also create a weak reference to the value within an Rc<T> instance by calling Rc::downgrade and passing a reference to the Rc<T>.

When you call Rc::downgrade, you get a smart pointer of type Weak<T> and weak_count will be increased by 1.

The difference is the weak_countdoesn’t need to be 0 for the Rc<T> instance to be cleaned up.

Because the value that Weak<T> references might have been dropped, to do anything with the value that a Weak<T> is pointing to, you must make sure the value still exists.

Do this by calling the upgrademethod on a Weak<T> instance, which will return an Option<Rc<T>>.

Create a tree data structure

1 | |

Fearless concurrency

Using thread to run code simultaneously

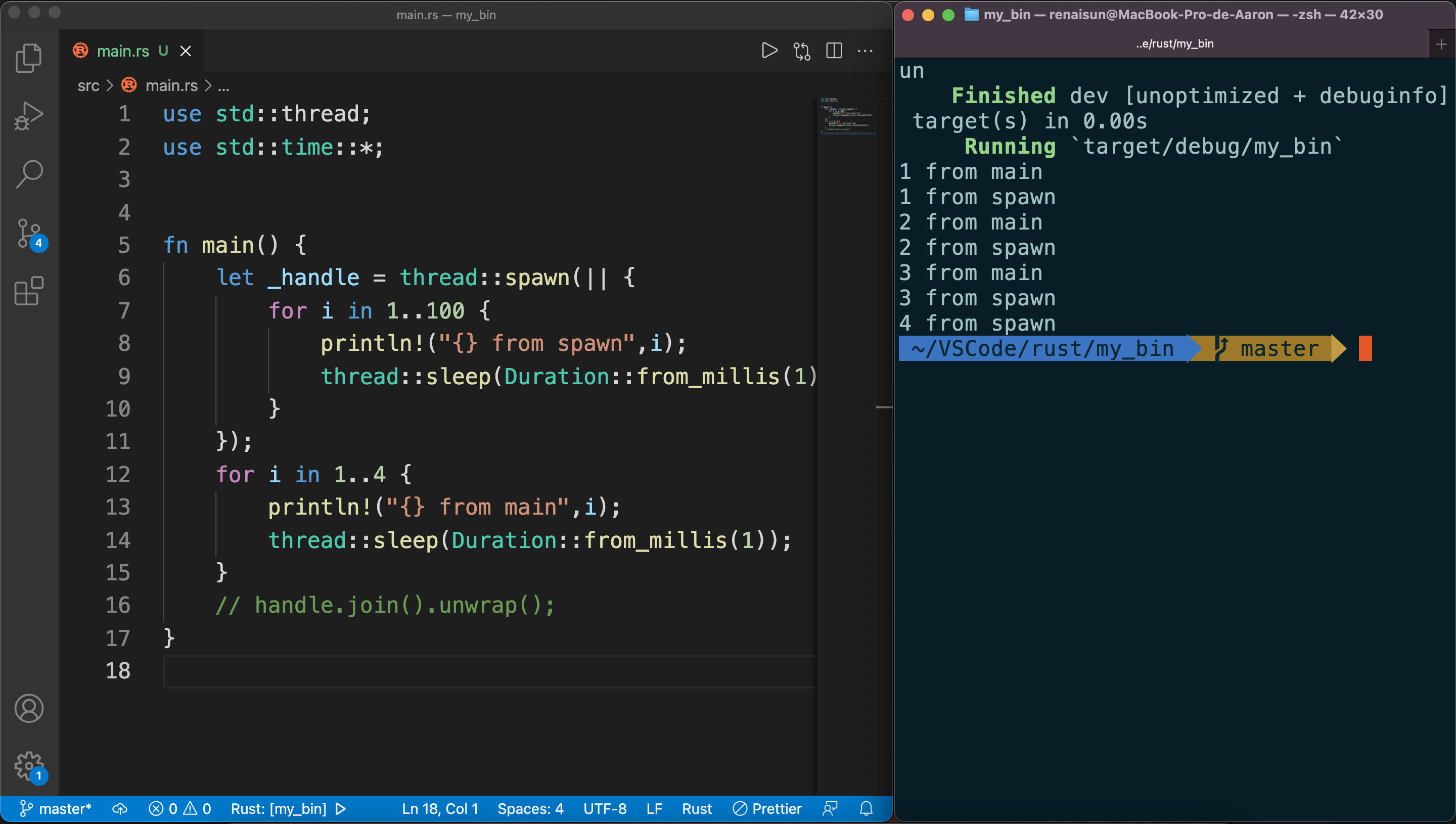

Creating a new thread with spawn

The threads will probably take turns, but it depends on how the OS operates them.

The spawn thread only print out 4 because of the shutdown of main thread.

Waiting all threads to finish using join

1 | |

Using move closures with threads

The move closure allows you to use data from one thread in another thread.

problem introduce

1 | |

When println in substhread using the reference to v, v may has been dropped by main thread, which causes the invalid reference.

However, if we do this:

1 | |

the drop function in main thread will be also receive a invalid reference.

Using message passing to transfer data between threads

Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

One major tool Rust has for accomplishing message-sending concurrency is the channel.

channel consists of :

- transmitter

- receiver

create channel

1 | |

mpsc is short for multiple producer, single consumer

create thread and send message

1 | |

the receiveing end of the channel

two methods:

recvwill block the main thread’s execution and wait until a value is sent down the channel

try_recvwill NOT block

We could write a loop that calls

try_recvevery so often, handles a message if one is available, and otherwise does other work for a little while until checking again.

Channels and ownership transference

In this code(will not be compiled)

1 | |

The problem is that if there’s modifications and results brought by inconsistent or nonexistent data in other thread, this will cause unexpected result.

Sending multiple values and seeing the receiver waiting

1 | |

In the main thread, we’re NOT calling the recv function explicitly anymore: instead, we’re treating rx as an iterator.

For each value received, we’re printing it. When the channel is closed, iteration will end.

Shared-state concurrency

Mutex(mutual exclusion) allows only one thread to access some data at any given time.

To access the data in a mutex, a thread must first signal that it wants access by asking to acquire the mutex’s lock. The lock is a data structure that is part of the mutex that keeps track of who currently has exclusive access to the data. Therefore, the mutex is described as guarding the data it holds via the locking system.

Mutex<T>

Example:

1 | |

To access the data inside the mutex, we use

lockmethod to acquire the lock.This call will block the current thread.

The call to

lockwould fail if another thread holding the lock panicked.

Mutex<T> returns a MutexGuard smart pointer which has implementation of Deref and Drop

Sharing Mutex<T> between multiple threads

1 | |

This cause compile error. The counter value was moved in the previous iteration of the loop. So Rust is telling us that we can’t move the ownership of lock counter into multiple threads.

Atomic reference counting with Arc<T>

Arc<T> is a type like Rc<T> that is safe to use in concurrent situations.(atomically reference counted)

Thread safety comes with a performance penalty that you only want to pay when you really need to.

Example(TODO)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23use std::sync::{Mutex, Arc};

use std::thread;

fn main() {

let counter = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

let mut handles = vec![];

for _ in 0..10 {

let counter = Arc::clone(&counter);

let handle = thread::spawn(move || {

let mut num = counter.lock().unwrap();

*num += 1;

});

handles.push(handle);

}

for handle in handles {

handle.join().unwrap();

}

println!("Result: {}", *counter.lock().unwrap());

}

Similarities between RefCell<T>/Rc<T> and Mutex<T>/Arc<T>

Rust can’t protect you from all kinds of logic errors when you use Mutex<T>. Using Rc<T> came with the risk of creating reference cycles. Similarly, Mutex<T> comes with the risk of creating deadlocks.

Extensible concurrency with Sync and Send traits

Two concurrency concepts are embedded in the language: the std::marker traits

SyncSend

Allowing transference of ownership between threads with Send

Send marker traits indicates that ownership of values of the type can be transferred between threads.

Almost every Rust type is Send but there are some exceptions.

Rc<T>: cannot beSendbecause if you clone anRc<T>value and tried to transfer ownership of the clone to another threadd, both threads might update the reference count at the same time.raw pointers

Allowing access from multiple threads with Sync

Sync marker trait indicates that it’s safe for that type to be referenced from multiple threads.

not Sync:

Rc<T>RefCell<T>Cell<T>

is Sync:

Mutex<T>Arc<T>

Implementing Send and Sync manually is unsafe

As marker traits, they don’t even have any methods to implement. They’re just useful for enforcing invariants related to concurrency.

Patterns and matching

All the places patterns can be used

match arms

1 | |

_ can be used to ignore value not specified.

if let expressions

example:

1 | |

while let conditional loops

That is similar to while(condition){} in c++

1 | |

for loops

In a for loop, the pattern is the value that directly follows the keyword for, so in for x in y the x is the pattern.

Example:

2

3

4

5

6

7fn main() {

let v = vec!['a', 'b', 'c'];

for (index, value) in v.iter().enumerate() {

println!("{} is at index {}", value, index);

}

}we will get:

a is at index 0

…

enumerate method is to adapt an iterator to produce a value and that value’s index in the iterator, placed into a tuple.

let statements

in variable assignment:

1 | |

_ and .. can also be used to ignore values in the tuple.

Function parameters

match tuple as argument:

1 | |

Also, we can also use patterns in closure parameter lists in the similar way.

Refutability: whether a pattern might fail to match

Patterns come in two forms:

- refutable

- irrefutable: will match for any possible value passed

let and for loops can only accept irrefutable patterns.

if let and while let accept both refutable and irrefutable patterns.

Pattern syntax

Matching literals

match patterns against literals directly:

1 | |

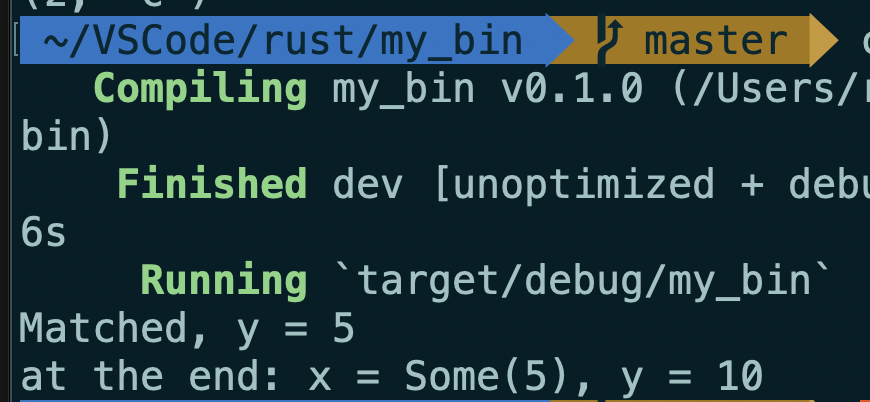

Matching named variables

Named variables are irrefutable patterns that match any value.

matchstarts a new scope, variables declared as part of a pattern inside thematchexpression will shadow those with the same name outside thematchconstruct.Example:

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12fn main() {

let x = Some(5);

let y = 10;

match x {

Some(50) => println!("Got 50"),

Some(y) => println!("Matched, y = {:?}", y),

_ => println!("Default case, x = {:?}", x),

}

println!("at the end: x = {:?}, y = {:?}", x, y);

}

Multiple patterns

| syntax means or.

Matching ranges of values with ..=

1 | |

for example, 1..=5 is equal to 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

Ranges are only allowed with numeric values or char values

Destructuring to break apart values

We can also use patterns to destructure structs, enums, tuples, and references to use different parts of these values.

Destructuring structs

Example:

1 | |

- There’s no restriction for sequence of x and y.

- To destruct structs into the same names of variables as the field in structs:

1 | |

- destructure with literal values as part of the struct pattern rather than creating variables for all the fields.

1 | |

Destructuring enum variants

Example:

1 | |

Destructuring nested structs and enums

Example:

1 | |

Destructuring structs and tuples

We can mix, match and nest destructuring patterns in more complex ways.

1 | |

Ignore values in a pattern

ignore an entire value with _

1 | |

Ignoring a function parameter can be especially useful in some cases, for example, when implementing a trait when you need a certain type signature but the function body in your implementation doesn’t need one of the parameters.

ignore parts of the value with _

1 | |

ignore an unused variable by starting its name with _

1 | |

Note that there is a subtle difference between using only _ and using a name that starts with an underscore. The syntax _x still binds the value to the variable, whereas _ doesn’t bind at all.

Example will provide an error:

1 | |

An unused variable starting with an underscore still binds the value, which might take ownership of the value

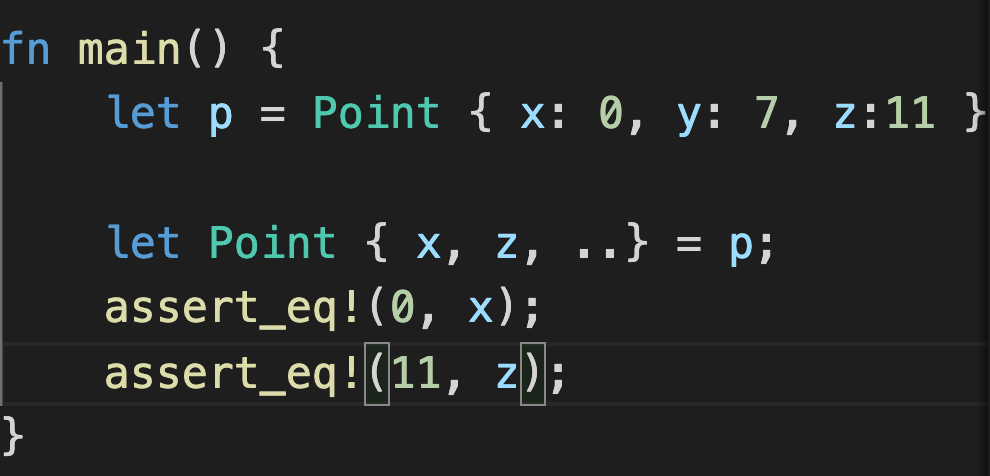

ignore remaining parts of a value with ..

We can use the .. syntax to use only a few parts and ignore the rest, avoiding the need to list underscores for each ignored value.

Note that .. can only be used once per tuple pattern to prevent the ambiguity of parts referred.

Extra conditionals with match guards

A match guard is an additional if condition specified after the pattern in a match arm that must also match, along with the pattern matching, for that arm to be chosen.

1 | |

@ bindings

@ lets us create a variable that holds a value at the same time we’re testing that value to see whether it matches a pattern.

Example:

1 | |

Advanced features

Unsafe rust

Why it exists?

- Static analysis is conservative. Although the code might be okay, if the Rust compiler doesn’t have enough information to be confident, it will reject the code. In these cases, unsafe code can let compiler to trust you to use the code at our own risk.

- The underlying computer hardware is inherently unsafe.

Unsafe superpowers

unsafe keyword can let the block that holds the unsafe code:

- Dereference a raw pointer

- Call an unsafe function or method

- Access or modify a mutable static variable

- Implement an unsafe trait

- Access fields of

union

unsafe doesn’t turn off the borrow checker or disable any other of Rust’s safety checks

To isolate unsafe code as much as possible, it’s best to enclose unsafe code within a safe abstraction and provide a safe API. Wrapping unsafe code in a safe abstraction prevents uses of unsafe from leaking out into all the places that you or your users might want to use the functionality implemented with unsafe code, because using a safe abstraction is safe.

Dereferencing a raw pointer

Raw pointers can be mutable or immutable:

*const T*mut T

Different from references and smart pointers, raw pointers:

- Are allowed to ignore the borrowing rules by having both immutable and mutable pointers or multiple mutable pointers to the same location

- Aren’t guaranteed to point to valid memory

- Are allowed to be null

- Don’t implement any automatic cleanup

Create raw pointers from references

2

3let mut n = 5;

let r1 = &num as *const i32;

let r2 = &mut num as *mut i32;

Creating a raw pointer to an arbitrary memory address

2let addr = 0x012345usize;

let r = addr as *const i32;

dereferencing raw pointers within an

unsafeblock

2

3

4unsafe {

println!("r1 is: {}", *r1);

println!("r2 is: {}", *r2);

}

Creating a pointer does no harm; it’s only when we try to access the value that it points at that we might end up dealing with an invalid value.

Note: we created *const i32and *mut i32 raw pointers that both pointed to the same memory location, where num is stored. If we instead tried to create an immutable and a mutable reference to num which** potentially creates a data race**, the code would not have compiled because Rust’s ownership rules don’t allow a mutable reference at the same time as any immutable references.

Calling an unsafe function or method

By calling an unsafe function within an unsafe block, we’re saying that we’ve read this function’s documentation and take responsibility for upholding the function’s contracts.

1 | |

Bodies of unsafe functions are effectively unsafe blocks, so to perform other unsafe operations within an unsafe function, we don’t need to add another unsafe block.

Creating a safe abstraction over unsafe code

Take split_at_mut as an example, we may implement the function like this:

1 | |

Rust’s borrow checker can’t understand that we’re borrowing different parts of the slice; it only knows that we’re borrowing from the same slice twice. Borrowing different parts of a slice is fundamentally okay because the two slices aren’t overlapping.

use an

unsafeblock, a raw pointer, and some calls to unsafe functions to make the implementation ofsplit_at_mutwork.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use std::slice;

fn split_at_mut(slice: &mut [i32], mid: usize) -> (&mut [i32], &mut [i32]) {

let len = slice.len();

let ptr = slice.as_mut_ptr();

assert!(mid <= len);

unsafe {

(slice::from_raw_parts_mut(ptr, mid),

slice::from_raw_parts_mut(ptr.add(mid), len - mid))

}

}

}

Using extern functions to call external code

**Functions declared within extern blocks are always unsafe to call from Rust code. **

extern, that facilitates the creation and use of a Foreign Function Interface (FFI). An FFI is a way for a programming language to define functions and enable a different (foreign) programming language to call those functions.

1 | |

Within the extern "C" block, we list the names and signatures of external functions from another language we want to call. The "C" part defines which application binary interface (ABI) the external function uses: the ABI defines how to call the function at the assembly level. The "C" ABI is the most common and follows the C programming language’s ABI.

Calling Rust functions from other languages.

#[no_mangle]annotation to tell the Rust compiler not to mangle the name of this function. Manglingis when a compiler changes the name we’ve given a function to a different name that contains more information for other parts of the compilation process to consume but is less human readable. Every programming language compiler mangles names slightly differently.

2

3

4#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn call_from_c() {

println!("Just called a Rust function from C!");

}

Accessing or modifying a mutable static variable

If two threads are accessing the same mutable global variable, it can cause a data race.

So it’s preferable to use the concurrency techniques and thread-safe smart pointers.

Implementing an unsafe trait

A trait is unsafe when at least one of its methods has some invariant that the compiler can’t verify.

Both adding the unsafekeyword before trait and marking the implementation of the trait as unsafe are necessary.

1 | |

Accessing fields of a union

A union is similar to a struct, but only one declared field is used in a particular instance at one time. Accessing fields of union must be worked with unsafe, because Rust can’t guarantee the type of the data currently being stored in the union instance.

Advanced traits

Specifying Placeholder Types in Trait Definitions with Associated Types

Associated types connect a type placeholder with a trait such that the trait method definitions can use these placeholder types in their signatures.

For example,

1 | |

Item is a placeholder type. Associated types might seem like generics

However, if using generics, you have to annotate the types in each implementation.

Default generic type parameters and operator overloading

Specifying a default concrete type for the generic type: <PlaceholderType=ConcreteType>

Rust doesn’t allow custom own operators or overloading arbitrary operators. Things we can do is to overload operations and corresponding traits listed in std::ops

Take add traits as example,

1 | |

Rhs: generic type parameter(right hand side)Rhs=Self: default type parameters

If we want to implement the Add trait where we want to customize the Rhs type rather than using the default:

1 | |

Use cases of default type parameters:

- extend a type without breaking existing code.

- allow customization in specific cases most users won’t need

Fully qualified syntax for disambiguation: calling methods with the same name

Imaging there’re two traits that have a method of same name as others.

1 | |

- Pilot – fly

- Wizard – fly

- Human – fly

To specify the trait you wanna call:

1 | |

However, associated functions that are part of traits don’t have a self parameter.

1 | |

In this case, if you want to call Animal trait that is implemented in Dog, you cannot just use Animal::baby_name(). Instead, we use fully qualified syntax

1 | |

1 | |

For associated functions, there would not be a receiver: there would only be the list of other arguments.

Use spertraits to require one trait’s functionality within another trait

Sometimes, you might need one trait to use another trait’s functionality. In this case, you need to rely on the dependent trait also being implemented. The trait you rely on is a supertrait of the trait you’re implementing.

Use the newtype pattern to implement external traits on external types

Orphan rule: we’re allowed to implement a trait on a type as long as either the trait or the type are local to our crate.

It’s possible to get around this restriction using the newtype pattern.

For example, if we want to implement Display on Vec<T>, which the orphan rule prevents us from doing so because Display trait and the Vec<T> type are defined outside our crate.

1 | |

Advanced types

Using the newtype pattern for type safety and abstraction

Another use of the newtype pattern is in abstracting away some implementation details of a type: the new type can expose a public API that is different from the API of the private inner type if we used the new type directly to restrict the available functionality.

The newtype pattern is a lightweight way to achieve encapsulation to hide implementation details.

Create type synonyms with type aliases

syntax:

1 | |

this can be used to reduce the repetition.

In std::io, a type alias declaration is defined:

1 | |

This line shows that std::io::Result<T> is equivalent to Result<T,E> with E filled in as std::io::Error

The never type that never returns any value

The special type named ! is known in type theory lingo as the empty type. For example,

1 | |

What is the use case of never type?

case #1

1 | |

Because match arms must all return the same type and we cannot return a u32 if there’s parsing error.

Here continue has a ! value. In a formal way, type ! can be coerced into any other type.

case #2

In the implementation of unwrap function in Option<T>, what is done to achieve returns a value or panic?

1 | |

panic!has type!- then it’s converted into type

T

Dynamically Sized Types and sized trait

dynamically sized types: DSTs or unsized types

The same type in Rust must take up same amount of space.

&str stores the starting address of string and its length. So we can know a single &str variable takes up 2*usizes length.

That is the way in which DSTs are used in Rust: they have an extra bit of metadata that stores the size of the dynamic information. The golden rule of dynamically sized types is that we must always put values of dynamically sized types behind a pointer of some kind.

Traits is actually a DST that we can refer to by using the name of the trait.

Use traits as trait objects such as:

&dyn TraitBox<dyn Trait>Rc<dyn Trait>

Sized trait is used to determine whether or not a type’s size is known at compile time.

In addition, Rust implicitly adds a bound on Sized to every generic function:

1 | |

is actually treated as though we had written this:

1 | |

By default, generic functions will only work on types that have a known size at compile time.

A special syntax to refer “may not”

1 | |

?Sized means T may or may not be Sized. This syntax is only available for Sized.

Note that as T may not be Sized, we should use it behind some kind of pointer.

Advanced functions and closures

Function can be passed as a type function pointerfn.

For example:

1 | |

Note that:

fnimplement all three of the closure traits(Fn,FnMut, andFnOnce)- When interfacing with external code doesn’t have closures, accepting

fnwould be useful.

An example for using either a closure or function:

1 | |

Here, we’re using the to_string function defined in the ToString trait, which the standard library has implemented for any type that implements Display.

Another example

We have another useful pattern that exploits an implementation detail of tuple structs and tuple-struct enum variants.

The initializers are actually implemented as functions returning an instance that’s constructed from their arguments.

So:

1 | |

Returning closures

If we want to return a closure directly, :

1 | |

The compile error references the Sized trait. Rust doesn’t know how much space it will need to store the closure. We can use a trait object.

1 | |

“Using Trait Objects That Allow for Values of Different Types”

Macros

The term macro refers to a family of features in Rust: declarative macros with macro_rules! and three kinds of procedural macros:

- Custom

#[derive]macros that specify code added with thederiveattribute used on structs and enums - Attribute-like macros that define custom attributes usable on any item

- Function-like macros that look like function calls but operate on the tokens specified as their argument

The difference between macros and functions

Fundamentally, macros are a way of writing code that writes other code, which is known as metaprogramming.

println! and vec! Macros are expanded to produce more code than the code written manually.

Macros have some additional powers that functions don’t.

- Macros can take a variable number of parameters while function must declare fixed params and numbers of them.

- Macros are expanded before the compiler interprets the code. So, a macro can implement a trait on a given type which need to be done at compile time.

- The downside to implementing a macro instead of a function is that macro definitions are more complex than function definitions because you’re writing Rust code that writes Rust code.

- You must define macros or bring them into scope before you call them in a file, as opposed to functions you can define anywhere and call anywhere.

Declarative macros with macro_rules! for general metaprogramming

Most common form of macros is declarative macros

what declarative macros do is similar to pattern matching. The arguments that macros receive will be passed and compared with the structure of that source code.

Take how the vec! macro is defined as example: (vec! Macro in standard library is slightly different)

1 | |

#[macro_export]means this macro shoud be made available whenever the crate in which the macro is defined is brought into scope.- the name(vec) end without

! - macro patterns are matched against Rust code structure rather than values.

Ref:

Procedural macros for generating code from attributes

Procedural macros act more like functions.

- custom derive

- Attribute-like

- Function-like

The defitions must reside in their own crate with a a special crate type.

1 | |

some_attributeis a placeholder for using a specific macro.- The

TokenStreamtype is defined by theproc_macrocrate that is included with Rust and represents a sequence of tokens.

Custom derive macro

1 | |

#[derive(HelloMacro)]annotation is to get default implementation of the hello macro function- We can’t yet provide the

hello_macrofunction with default implementation that will print the name of the type the trait is implemented on: Rust doesn’t have reflection capabilities, so it can’t look up the type’s name at runtime - If we create crate

foo, a custom derive procedural macro crate is calledfoo_derive.- To use these crates, both of them must be added as dependencies and bring them both into scope

- If we change the trait definition in

foo, implementation offoo_derivemust be changed too.

Steps:

Create a custom library

Modify its

Cargo.tomldeclare the crate as a procedural macro crate

add dependencies:

synandquoteFinally the whole file would look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6[lib]

proc-macro = true

[dependencies]

syn = "1.0"

quote = "1.0"

Edit the source code

This won’t compile yet. ( proc_marcro is included in Rust )

1 | |

code is split into two parts:

- parsing the

TokenStream - transforming the syntax tree: this makes writing a procedural macro more convenient.

syncrate parses Rust code from a string into a data structure that we can perform operations on.quotecrate turnssyndata structures back into Rust code- The

hello_macro_derivefunction will be called a user specifies#[derive(HelloMacro)]on a type. This is possible because we’ve annotated thehello_macro_derivefunction here withproc_macro_deriveand specified the name,HelloMacro, which matches our trait name;

- The following example shows parsed data from

struct Pancakes:

1 | |

- An example of impl_hello_macro

1 | |

ast.identreturn the ident field inIdentquote!macro is to define the rust code that we want to returnintomethod convert the result ofquote!macro toTokenStreamtype.#namewill be replaced byquote!with the value inname. This is a kind of templating mechanic.stringify!Macro turns the expression into a string literal at compile time.

Then manually specify the path of dependencies:

1 | |

Attribute-like macros

- Derive attribute only works for structs and enums

- Attributes can be applied to other items like functions.

An example use case of attributes

1 | |

The signature of the macro definition function would look like this:

1 | |

attris the contents of the attribute:GET,"/"in this caseitemis the body of the item the attribute is attached to:fn index(){}and the rest of the function’s body in this case.

Function-like macros

Function-like macros define macros that look like function calls.

- Take unknown number of arguments

- ake a

TokenStreamparameter and their definition manipulates thatTokenStreamusing Rust code as the other two types of procedural macros do

An example of function-like macro:

1 | |

This macro would parse the SQL statement inside it and check that it’s syntactically correct, which is much more complex processing than a macro_rules! macro can do.

The sql! macro’s signature would look like this:

1 | |